Are there different types of nuclear reactor?

Nuclear reactors come in many different shapes and sizes. Most are large enough to power major cities, and small reactors are being developed to complement them. Most use water to cool their cores, whilst others use gas or metals.

About 425 reactors globally, ranging in size from 30-1660MW, are water-cooled. There are two major types of water-cooled reactor: light water reactors (which use normal water) and heavy water reactors (which use a chemically distinct type of water). There are three major reactor design families under the umbrella of water-cooled reactors currently in use:

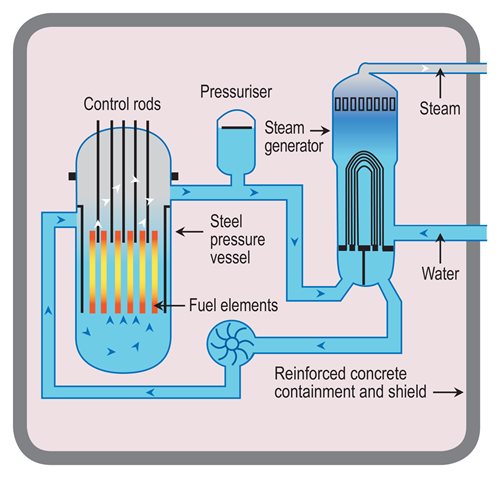

Pressurized water reactors (PWRs) make up almost 70% of the global reactor fleet. The design is distinguished by having a primary cooling circuit which flows through the core of the reactor, and a secondary circuit in which steam is generated to drive the turbine. Water in the primary circuit is prevented from boiling by pressurising the reactors. Water in the secondary circuit is under less pressure and therefore boils, turning the turbine to generate electricity.

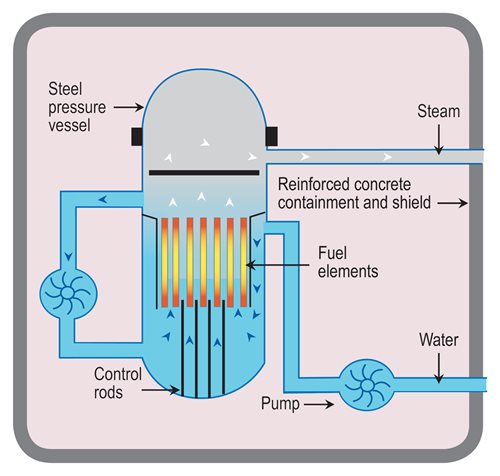

Boiling water reactors (BWRs) are the second most common reactor type globally, making up approximately 15% of the global fleet. Unlike PWRs, this design has a single circuit in which water is held at a pressure that allows it to boil. The steam generated in the reactor is fed directly to the turbine. BWRs are primarily found in the US, Japan, Sweden and Taiwan.

Pressurized heavy water reactors (PWHRs) are the third most common reactor type, making up 11% of the global fleet. The design uses heavy water, a chemically different form of water, to cool and control the nuclear reactions. By using heavy water, it is possible to use naturally-occurring uranium as fuel, rather than the enriched fuel used in PWRs and BWRs. Heavy-water reactors are mostly associated with Canada, but they are also used in India, Argentina, Romania, Pakistan and China.

Small modular reactors (SMRs)

SMRs are not a distinct type of reactor, but rather a family of different reactor designs which are smaller than most reactors currently in operation. Light water SMRs are likely to be towards the end of the 2020s, with broad deployment taking place in the early 2030s. More novel designs will take longer to reach commercialization. There are many different designs and sizes proposed, ranging from just a few megawatts to several hundred.

The Akademik Lomonosov, the world’s first floating nuclear power plant, is an SMR (Image: Rosatom).

SMRs offer a range of different benefits which complement large reactors. Given their size, small reactors are well-suited for remote areas and in grids that are too small to host a gigawatt-scale nuclear reactor. Additionally, a further benefit of SMRs is the prospect of so-called modularity, with most, if not all, components of the reactors being manufactured and assembled in a factory before being shipped to a site to be installed.

If you want to find out more about small modular reactors, visit our Information Library.

Nuclear designs for the future

Whilst most current reactors use water to cool the core, there is ongoing research and development looking at reactors that use liquid metals, molten salts or gases as coolant. The development of these reactors could offer more efficient nuclear power, with new and exciting applications. Many non-water reactor types have successfully been operated across the world for many years, mostly at experimental level.

The Beloyarsk Nuclear Power Plant, Russia, home to two sodium-cooled fast-neutron reactors (Image: Rosatom).

Liquid metal fast reactors (LMFRs) use different liquid metals (e.g. sodium, lead) to cool the core. Liquid metal reactors can be fuelled with uranium in metallic form (current reactors mostly use uranium in ceramic form), as well as recycled nuclear waste (i.e. plutonium, minor actinides). The world’s only currently operational fast reactors are the sodium-cooled BN-600 and BN-800 reactors – both located at the Beloyarsk Nuclear Power Plant in Russia.

Molten salt reactors (MSRs) use salts as coolant, with either solid fuel rods (similar to current reactors) or with the fuel dissolved in the salt itself. MSRs can use a range of fuels, such as uranium, plutonium, actinides from nuclear waste and thorium, depending on whether they are operating as fast reactors. As MSRs can operate at high temperatures, they can be used to generate hydrogen and heat for different industrial applications.

High-temperature gas-cooled reactors (HTGRs) are cooled by gas (e.g. helium, carbon dioxide) with the uranium fuel being either in the shape of fuel rods (surrounded by graphite blocks) or fuel particles (uranium 'balls' covered with different materials such as silicon carbide). HTGRs operate at very high temperatures (>800°C) and are well suited for the generation of synthetic fuels and district and industrial heat.

Many reactors under development are so-called 'fast' reactors, where the neutrons from the nuclear chain reaction are not slowed down, unlike in conventional reactors where the reaction is moderated by water and/or graphite. Fast reactors represent a technological step forward and will be capable of recycling nuclear wastes from current nuclear reactors, and radically increasing the amount of energy we can get from nuclear fuel – from approximately 5% today to 90%+.

If you want to find out more about reactor designs of the future, visit our Information Library.

Nuclear fusion reactors

Nuclear fusion is the process that powers stars, where hundreds of millions of tonnes of hydrogen are fused into helium, generating immense amounts of heat and light. Research into nuclear fusion has taken place since the 1940s. Just like nuclear fission, fusion is a low-carbon energy source, which emits no greenhouse gases or other pollutants. Fusion is a promising technology with abundant fuels (a bathtub of water and the lithium from a laptop battery would be enough to supply a lifetime’s worth of electricity for one person), but it is unlikely that the first commercial nuclear fusion power plant will be operational before the 2050s.

If you want to find out more about nuclear fusion, visit our Information Library.

Most of the world’s experimental fusion reactors are doughnut-shaped vessels, called tokamaks (Image: ITER).